Language and Trees: Scottish Gaelic and Wilderness

Many organisations have settled on exploring a particular era of linguistic history in the British Isles, namely the Brythonic (asides from Breton) and Goidelic languages. Previous languages such as Pictish and its written form of Ogham and the languages of settlers such as the Romans, and later languages brought by European settlement are not often used in linking British wilderness with culture. Earlier this month, I visited Trees for Life's Dundreggan site for research, and began thinking about the use of Scottish Gaelic culture and language in British rewilding and conservation.

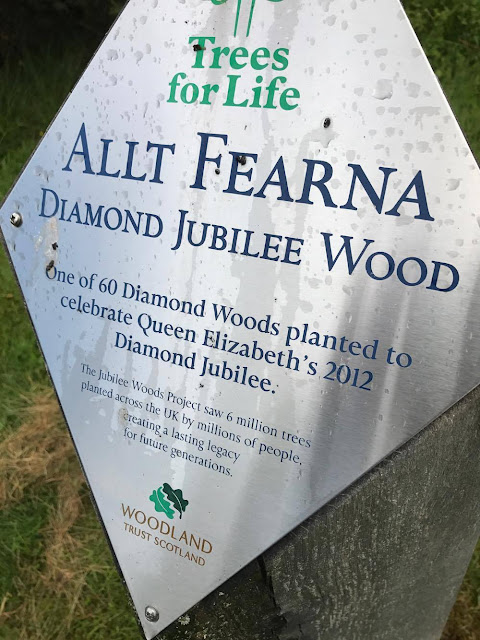

One of the Gaelic place names found at the Dundreggan Conservation Estate. Allt Fearna apparently means 'Alder Stream.'

Dundreggan prides itself on the existing place names within its midst; a leaflet welcoming visitors reserves a whole section to describe the 'Gaelic Landscape.' Dundreggan comes from

"Duldreagain, meaning riverside meadow of the dragon," while streams and burns are identified as "Allt a' Choire Bhuidhe" (stream of the yellow corrie) "Allt Ruadh" (Red Burn) and the hills "Binnilidh Bheag" and "Binnilidh Mhor" being the wee buttock and the big buttock. Rather than being left low on local maps, or worse, forgotten, these place names are brought to the fore of the conservation estates image, with information about their meanings found in the posters and leaflets at the entrance to the estate.

The diverse, wild vegetation cover created at Dundreggan

It is not just at Dundreggan that entrenches wilderness in a Gaelic culture and language. Inverness museum has several information points on Gaelic names for flora and fauna and how these labels reflect Gaelic life. Adorning the stairs connecting the museum and the art gallery is a series on the Gaelic tree alphabet, a system of learning the Gaelic alphabet through matching the letters with names of trees. The tree alphabet, according to the display, has a supposed mixed origin in Medieval Ireland and Scotland, and even earlier in Pictish, but it was prominent in the Victorian period.

I have no real remark or conclusion to make, and am merely exploring my observations. It is interesting to note, however, that both the wildlife selected for connection and the languages used are all a drastic minority to their previous stature, but all facing a vivid modern discussion and hopeful revival.

The Aldross Wolf stone, a Pictish Carving, displayed at Inverness Museum. The museum uses this design on their sign, linking themselves with the extirpated wildlife of the Highlands, and the cultures and languages that would have interacted with it.

Comments

Post a Comment