Language and Trees: Scottish Gaelic and Wilderness

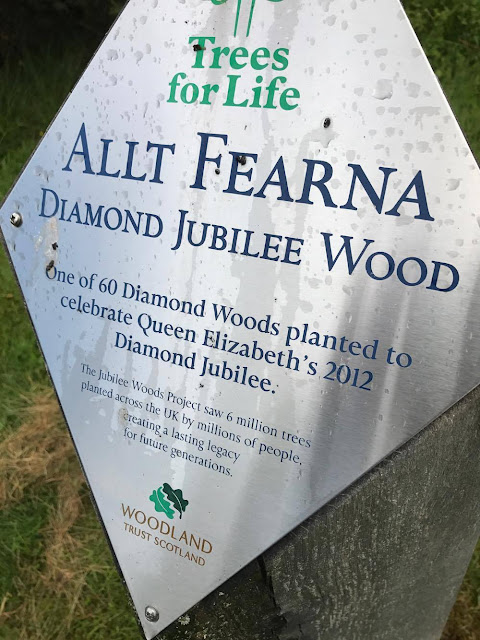

One of the things many conservationists, especially those involved in rewilding, in Scotland (or Britain in general) seem to turn to is the links between ancient British history and language and the wilderness that has since been drastically extirpated from the Isles. A consideration for the Celtic history of Britain can be found in texts such as George Monbiot's writings including his book Feral, which brought rewilding into British popular consciousness, and other texts that often highlight the plight of the Scottish or Welsh when faced with clearance and industrialised agricultural change. Organsiations similarly discuss the Celtic nature to Britain's wilderness, whether they are management trusts such as the Woodland trust, or rewilding organisations such as the Cambrian Wildwood project in Wales, or Trees for Life operating in Scotland. Many organisations have settled on exploring a particular era of linguistic history in the British Isles, namely the Brythonic (asides...